By Ben Gomes-Casseres | Originally in MARKETWATCH |

In this banner year for corporate deals, some have been impressive and others less so. Here are the top 10 that stand out to me, not because of size or drama, but for the lessons they contain.

Every business combination (and separation too) must follow three laws to succeed. They must have the potential to create value, they must be designed and managed to generate that value, and the gains from the deal must be shared effectively among the players. Some of these deals promise to fulfill those laws, but for others it is still hard to tell. Each deal does teach us something different: They are “best in class” winners:

1. Allergan-Pfizer: A tax-accountant’s dream. Pfizer Inc. had been maneuvering for more than a year to move its domicile out of the U.S. to a lower-tax jurisdiction. A bid to buy AstraZeneca PLC was resisted and shelved last year. In its deal with Allergan PLC it thinks it has overcome regulatory challenges. If approved, Pfizer will have finally gotten its tax inversion, by clever acrobatics and by snagging a partner big enough to make it a substantive merger. The acrobatics include the fact that Allergan is technically acquiring Pfizer — at a discount (or a premium for Allergan). This price differential was needed in part to make the inversion stick. But did Pfizer give up too much to get its tax dream? That depends on what substantive benefits the merger yields. So far, the company’s projections suggest modest synergies.

2. GSK-Novartis: The remix champion. Not the kind of “remix” popular in music, but the business kind — a reshuffling of assets that can create new value. The deal between GlaxoSmithKline PLC and Novartis AG set a standard early in the year for smart deal structuring that wasn’t surpassed. The complex deal and strategy was also exceptionally well-explained to the public. It included a swap of oncology and vaccines assets, a new joint venture for non-prescription drugs and a divestment to a third company, Eli Lilly & Co. The idea is to strengthen each business by focusing the resources of the two companies. Asset reshuffling in a multi-part deal like this is not uncommon (Sanofi SA and Ingelheim did one too this year), but often companies revert to a big merger instead — as the next winner shows.

3. Dow-DuPont: The remix challenger. The proposed mega-merger between Dow Chemical Co. and DuPont claims to be more than that. It bills itself as the precursor to a break-up that will yield three businesses. Investors are still a bit confused as to where precisely new value will be created, in the combination or the separation, how much gain will be generated, and by when. If this scheme to bulk up before slimming down works out, it will be a first, at least at this scale. But, as a challenger, only time will tell exactly what the multi-year deal entails. And that time will be noisy, as activists are involved on both sides. Activists’ involvement in this and other deals this year have driven a controversy around whether they help in value creation.

4. Dow-Corning: A piece of history. This deal flew under the radar of the previous one, but it is remarkable for its own sake. Dow Chemical is buying out Corning Inc. from the 50/50 joint venture that they’ve had since 1943. This company was a model for joint ventures. It showed that partnerships often work best when each parent exits the joint business, as both Dow and Corning did in silicone plastics. In today’s reversal, Dow says it now wants to integrate that business more closely in its materials business, and Corning is happy to let its share of that business go. Corning does stay part-owner of the high-tech venture spawned by the older joint venture, which is closer to its core today. Good partnership models teach lessons in both their making and their breaking.

5. Yahoo: The no-deal deal. Yahoo Inc. said “never mind” to its long-awaited spinoff of Alibaba shares, as it continues to seek ways to break itself up with a minimum of taxes. But break-up it will be — just a different move. The idea it’s considering now is to spin off the core Internet business, since that piece may well get a decent price from a telecom or media buyer. This is not a tall order, given that in its current incarnation, shareholders seem to value Yahoo’s core business at less than zero. Recall that Yahoo rejected a good offer from Microsoft a few years ago; ironic that it is now seeking a better home for its Internet assets. Yahoo is not alone in its cohort in going back and forth on its combination strategy. AOL went from its earlier failed mega-merger with Time Warner Inc. to selling itself to Verizon Communications Inc. this year.

6. GE Capital: The biggest exit. The assets of GE Capital that General Electric Co. has decided to sell to get out of the pure banking business are huge — clearly the biggest spin-off of the year. And it is part of a corporate redirection that is noteworthy in its own right. The banking exit is paired with a doubling down on industrial businesses. A few years ago, before the collapse of oil prices, GE bulked up in oil-and-gas-service businesses. Today it is turning to software to help it dominate the “Things” part of the Internet of Things. This strategy led to alliances with Cisco and Intel, a new kind of deal for GE. Whether the exit from banking leads to higher returns, therefore, depends on what the rest of GE does with the proceeds.

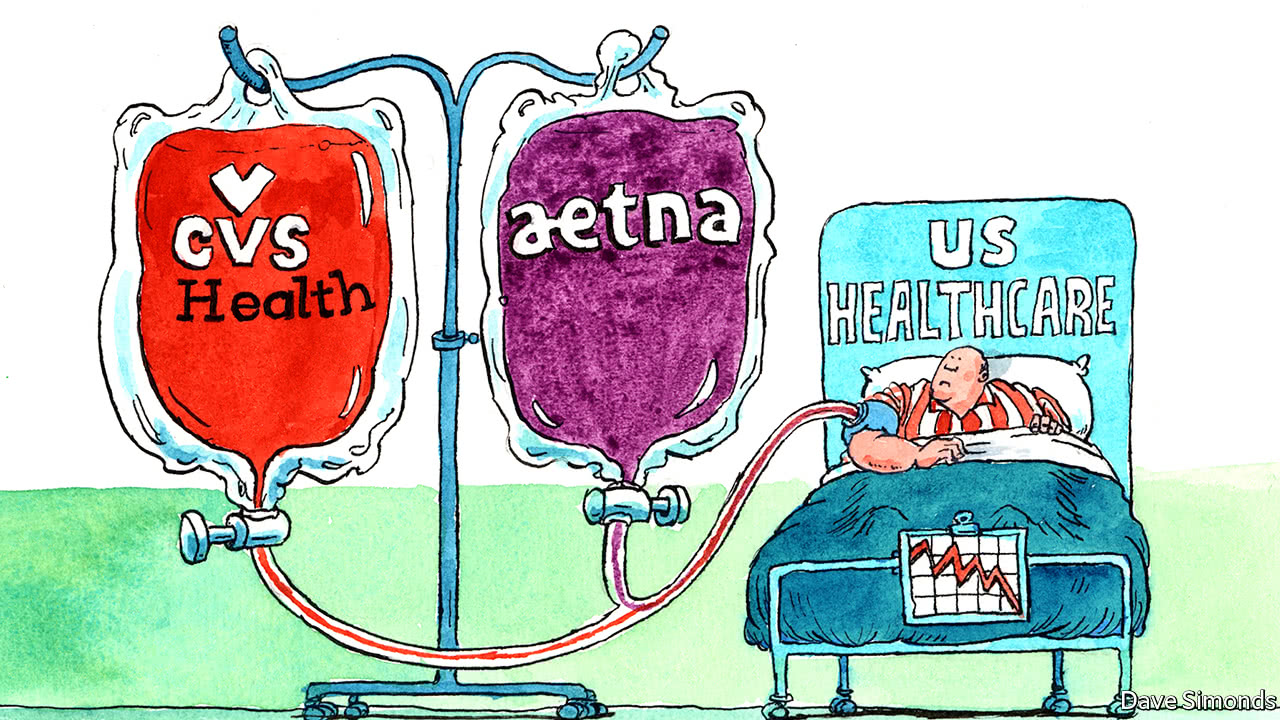

7. Budweiser-Miller: The big-is-beautiful boys strike again. While some large businesses are slimming down, others are bulking up in the hopes of even more economies of scale, or at least more market power. The merger of Anheuser-Busch InBev NV and SABMiller is the handiwork of 3G Capital, a private-equity group from Brazil, and follows on the heels of their merger of Kraft and Heinz last year. E. F. Schumacher’s “Small Is Beautiful” is not on their reading list. Consolidation is also all the rage in health services, where insurance companies have tied up, as have retailers and wholesalers. How far should such consolidation go? Once the real rationale — stated or unstated — becomes market power, not efficiency or innovation, then anti-trust authorities will take notice, as in the next case.

8. Staples-Office Depot: Anti-trust red line? At first, it looked as if Staples Inc. had a point about its merger with Office Depot Inc. not being anti-competitive. It has so many more online competitors (read: Amazon.com). today than last time regulators rejected its bid for Office Depot in 1997. But late in the year, the Federal Trade Commission declared it will sue to stop the merger. Apparently, going from two brick-and-mortar competitors to one is not a good thing in its eyes, regardless of the online alternatives. The regulatory limits to consolidation may also have been reached in telecoms, where the authorities frowned on merger proposals from T-Mobile US Inc. and AT&T Inc. and then T-Mobile and Sprint Corp. Cable companies Time Warner and Charter Communications Inc. are sitting by their phones, waiting to hear if they too crossed a red line.

9. Shell-BG: Wildcat bet. Oil companies are used to betting on what the right spot is to drill the next exploratory well. In buying British Gas Group PLC Royal Dutch Shell PLC is betting that gas prices will stop sliding and finally start rising. All the oil majors are making this bet, with Exxon Mobil Corp. in the lead with its major acquisitions of gas assets in prior years. The Shell bet feels different, and not just because the nations of the world have promised to get off fossil fuels — they know that is a tall order and will take time. It comes at a time when resource-based mergers are taking a beating, as Glencore PLC’s troubles show. Shell is clearly playing the long game, but it is a big bet.

10. IBM-Apple: Happy first birthday! The true lessons of a deal are always down the road, when we see how it is implemented. In this sense, International Business Machines Corp. and Apple Inc. celebrated a happy first year, reporting new products and services. And unlike deals in many companies, this one continues to have IBM’s top management’s attention well after the ink was dry. The lesson is that even old arch enemies can work together, when circumstances change to draw them together.

It is impossible to tell how these deals will turn out in time. But in a way they have served a purpose already — to remind us the importance of the strategy behind the deal. The drama of personalities and of large dollar signs make the front pages. What ultimately matters is whether they create value for stakeholders.