By Ben Gomes-Casseres

This blog was cited in The New York Times’s DealBook (January 30, 2018):

The effort focuses on the United States employees of JPMorgan Chase, Amazon and Berkshire Hathaway. Together, the companies have nearly one million employees (a portion of those, though, are outside of the United States.) That’s a lot of employees but relatively small when compared with 157 million people who had employer health care plans at the end of 2016, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Would the venture be able to scale up? Some experts are skeptical about that. Ben Gomes-Casseres, a professor of international business at Brandeis, wrote: “My bet is that JPMorgan and Amazon’s employees have pretty good health coverage, with plans that rank among the richest that the industry has to offer. If so, will these lead users be anxious to find a more cost-effective model? Will they even be willing to experiment with their coverage? And, beyond that – if they do develop a new approach, will it be helpful to the masses of employees at lesser companies, or, worse, the unemployed and uninsured?”

Here is the full article:

January 30, 2018 — The news this morning that Amazon, JP Morgan, and Berkshire Hathaway are joining in a healthcare alliance is spectacular. We have no details, and it feels from the outside as if the partners don’t have many details worked out yet either. So, what can we make of this news?

It looks like a trial balloon, launched in a hot climate. Whether this balloon will grow and rise high or the air will slowly fizzle out of it remains to be seen. This would not be the first grand alliance announced with fanfare that meets that fate.

The little we know so far raises more questions than it answers.

First, the partners are a singular group. They are not competitors or even natural partners, but they are marquis companies in their industries. If you need big names to get your balloon noticed, this does it. So, this is the talk of the town even if we know nothing about the strategy.

But grand alliances by big names are not assured of success. IBM, Motorola, and Apple formed a semiconductor alliance in the 1990s that fizzled. Daimler and Mitsubishi launched a big partnership around that time that never led to real projects. The dot-com era was full of grand deals that fizzled – Barney deals, they were called, in honor of the big hugs that the fluffy character would give kids on TV.

The second point to notice is the lead users that the group wants to serve – their own employees. All technologies that end up disrupting a market start by serving a niche market, before it expands to mainstream users. In this case, the lead users are likely among the most elite consumers of healthcare insurance and products.

My bet is that JP Morgan and Amazon’s employees have pretty good health coverage, with plans that rank among the richest that the industry has to offer. If so, will these lead users be anxious to find a more cost-effective model? Will they even be willing to experiment with their coverage? And, beyond that – if they do develop a new approach, will it be helpful to the masses of employees at lesser companies, or, worse, the unemployed and uninsured? This does not seem to be an answer to the health care crisis faced by these (large) segments of the US population.

The third point that seems clear from the little we know is that the partners currently are only buyers of health care products. Even if Amazon has scared incumbents with its threat of entering the healthcare supply chain, it has not done much yet, and indications are that this is a tough chain to break into. JP Morgan and Berkshire Hathaway know about finance and insurance, but neither actually operates a health insurance business. And, of course, none of them make drugs (pharma companies do that) or deliver healthcare services (doctors and hospitals do that).

So what capabilities do they bring to the table? Primarily, they are big buyers of (likely expensive) healthcare services for their employees. From this perspective, this looks like a purchasing cooperative – customers getting together to raise their bargaining power in the face of a consolidating health care supply chain.

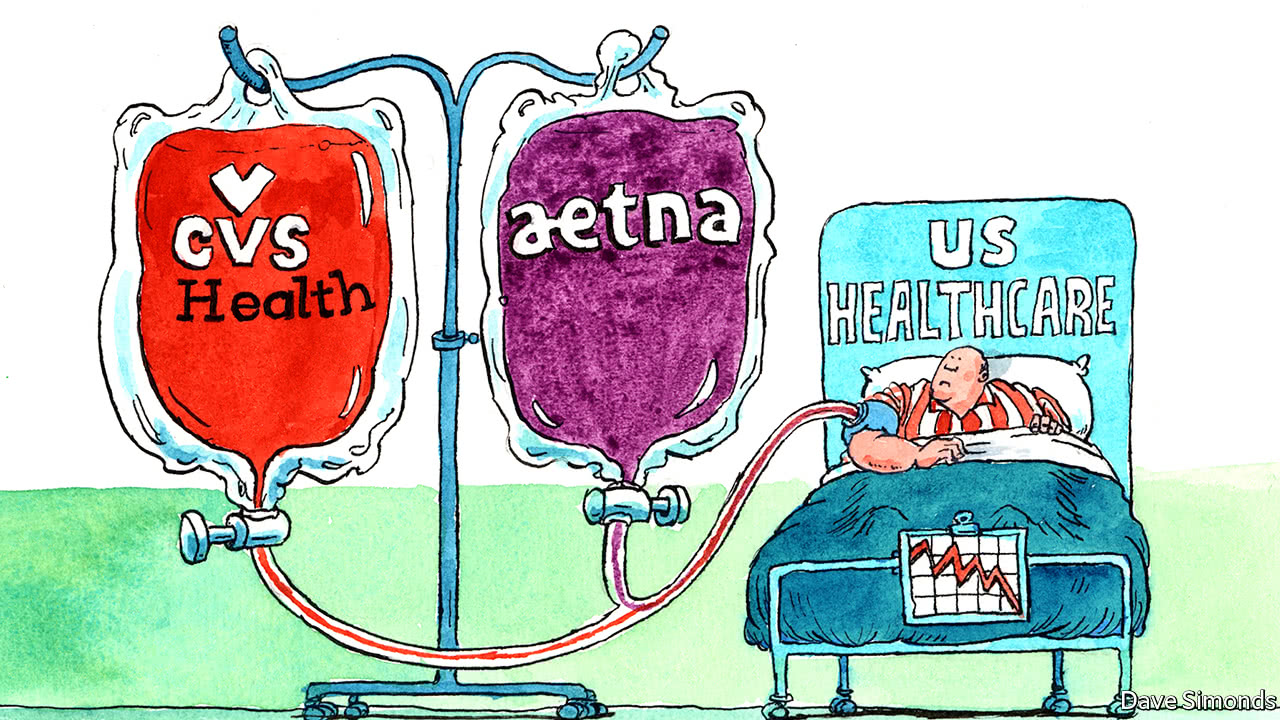

That could be the nub of the deal. (The White House says that is all it is.) We’ve seen consolidation up and down that chain – hospitals merging with hospitals, pharma companies merging, drugstores merging, insurance companies merging, and recently also mergers across the chain, as CVS and Aetna are doing. The classic strategic response when your suppliers are consolidating is to try to raise your clout as a buyer.

No doubt this purchasing cooperative will use the latest in online technology and crafty financial structuring. That is what the partners are good at. The executives appointed to lead the effort are skilled in pharma M&A (JPMorgan’s Marvelle Sullivan Berchtold), in logistics and human resources (Amazon’s Beth Galetti), and investment management (Berkshire Hathaway’s Todd Combs). But they can only succeed if the employees of their companies are receptive and if their CEOs and shareholders fully commit to invest in the long road ahead.

That requirement – investment from the parent companies – is the fourth point to note at this early stage. The announcement declares that this alliance will be a not-for-profit venture. That is puzzling, in part because the partners are not known for ignoring profits in their core operations. Plus, they should know that without the proper financial incentives to invest in a new model, the air will fizzle out of this balloon.

What is the incentive, then, if not profit? Well, it is profit anyway. The announced reason why these partners are getting together is to lower their healthcare costs – doesn’t that add to their bottom lines? Or do they intend to pass it all on to their employees? (Even if they did that, it will lower their total cost of employment.)

That is not a bad thing – without incentives for cooperation, even among well-intentioned partners, cooperation fails. Buyer cooperatives are no different. Disruptive alliances are no different. The partners had better own up to this and tell us the business model behind their trial balloon.

Benjamin Gomes-Casseres is an expert in alliance strategy and a professor at the International Business School, Brandeis University. He has been studying, teaching, and consulting on the strategy of business combinations for thirty years, and is the author of three books including Remix Strategy: The Three Laws of Business Combinations (HBR Press, 2015). To learn more about the ideas and tools he has developed, visit remixstrategy.com.