By Ben Gomes-Casseres | Originally in HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW |

Unlike the earth’s climate, the climate for business deals remained stubbornly unchanged in 2019 — or did it?

Business deals are both a lagging and a leading indicator of economic transformations. Some reflect past conditions; others signal emerging trends. A review of the past year’s most remarkable deals (and non-deals) can tell us where we have been and where we are going.

By various measures, M&A activity in 2019 was not as high as in previous years, but the pattern of deals is revealing and, in some aspects, new. Many of this year’s deals reflect industrial consolidation and digitization trends dating back decades. But there were also signs that the 2020s will usher in new trends in how we manage the power of technology. And we learned again that climate change is no joke, though we don’t know yet how businesses will respond. In time, business deals will reflect the transformation of our energy mix too.

Business-as-usual deals

Among the already established trends, Big Pharma this year continued to bulk up and smarten up. Since the 1990s, pharmaceutical companies have been consolidating to raise their bargaining power in the health care chain. They have also been hoovering up innovation from biotech startups. In 2019, Bristol-Myers Squibb acquired Celgene ($74 billion), Takeda acquired Shire ($62 billion), and Sanofi and Novartis both acquired companies in the $10 billion range. These deals do double duty — they bring new technologies to the big firms, and they also maintain a concentrated industry structure. At the same time, the big insurance mergers of yesteryear (CVS-Aetna and Cigna-Express Scripts) began the work of integration, though the jury is still out on their benefits for consumers.

Media and telecom companies also followed the well-established script to build market power. Three big mergers were finalized this year — Sprint and T Mobile ($26 billion), AT&T and Time Warner ($85 billion), and Disney and 21st Century Fox ($71 billion). Disney’s acquisitions in the last few years are fueling its aggressive offerings in streaming video. The streaming war between Disney, Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, Apple, and HBO had been brewing for a while, and is now being joined in full. This ecosystem will eventually lend itself to consolidation too, but we are not there yet. For now, it is a free-for-all to capture a new generation of media consumers moving off cable.

Industrial producers, too, played out a story that started a decade ago – the breakup of conglomerates. Dow broke itself up into three this year, as promised when it merged with DuPont two years ago. This two-step involved a merger to consolidate businesses, followed by spinoffs that enhanced focus in each business, while still maintaining their market power. In fact, the story of de-conglomeration was often two steps forward, one step backward. Danaher slimmed down only to bulk up again by buying General Electric’s biopharma unit ($21 billion). And GE, even after this sale, appears to be doubling down on its health business. In the aerospace and defense industry, United Technologies, which had broken itself into three, turned around and joined Raytheon in a merger of equals worth some $135 billion.

These were all big deals, but they were business-as-usual. What deals may be previews of the 2020s? In a curious way, the lack of certain kinds of deals is the biggest thing to watch.

Emerging trends in tech

There was renewed effort this year to contain the growth of tech. The idea that firms like Google, Facebook, and Amazon were getting too big and intrusive in our lives continued to gain ground in Washington. Google faced antitrust investigations in 50 states and the FTC head suggested it could pursue others. In mid-December, the FTC was reported to be considering an injunction against Facebook to stop it from integrating Instagram, WhatsApp, and Messenger – just in case the antitrust authorities decide later to break-up the company. These efforts may lead nowhere. But it would be surprising if the pressure didn’t cause big tech to shy away from large acquisitions. One large tech deal did close this year (IBM-Red Hat, $34 billion) and Salesforce acquired Tableau ($16 billion). But Apple, Google, and Amazon were relatively restrained, considering their hoards of cash — none of them spent more than $3 billion on a deal since 2017.

A related trend that gained ground in 2019 was the re-bordering of tech – the rise of a virtual wall between the Chinese and American spheres of influence in technology. Chinese investment in the United States dropped 90% in the last three years. The trade war started this, but the trend is fueled by a mutual suspicion between the countries’ elites and ruling regimes. Both sides believe that new industries such as artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, and social media are critical to national security and to the governance of society. In unprecedented fashion, the FCC banned Huawei from the U.S. market this year, citing data security concerns. Google already left China a decade ago over censorship. And anyway, Chinese companies dominate Chinese markets, and American firms, American markets. Technology firms famously enjoy network effects, but it looks like their networks will stop at the new border.

What do these old and new trends say about the transformation of our energy mix? Sadly, not much.

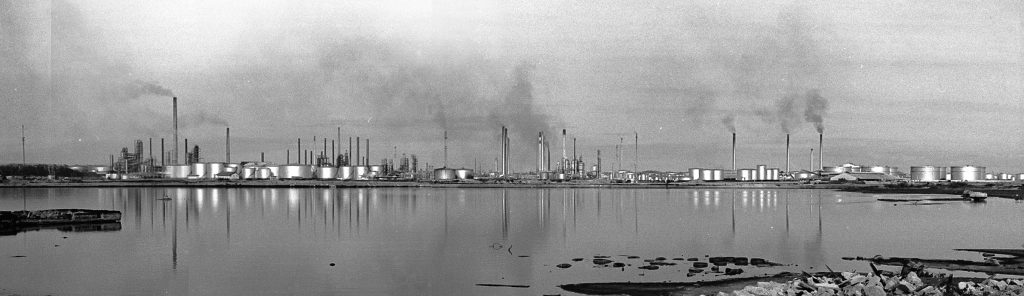

Responses to climate change

In terms of carbon emissions, the gap between where we are and where we should be is huge. Solar and wind are gaining ground, but it will be some time before our energy infrastructure can fully use their potential. The big oil companies continue to flirt with renewables startups; at least these partnerships make for good TV advertisements and perhaps soothe ESG investors. But worldwide, project financing and public R&D in renewable energy have actually been falling in recent years.

And yet, there was also trouble in the oil patch. Occidental acquired Anadarko ($38 billion), but the new company right away began to shed oil fields abroad to pay for the deal. And activist investor Carl Icahn is advocating for a reversal of this merger, arguing that it jeopardized the company’s value — this comes after he succeeded in helping scuttle the ill-fated merger of Fuji Film and Xerox. Occidental’s shareholders have not been happy, nor have shareholders of other oil companies: Exxon, Shell, and BP strained to pay dividends this year, and some are revaluing their assets in an environment of low prices and societal pressure. Aramco’s long awaited IPO did not help lift spirits of fossil fuel investors; its IPO valuation target was downgraded and it was listed only in the Riyadh market. Even so, it raised more money than any other IPO in history – a testament to the enduring power of oil.

The biggest deal news of the year was in fact not a deal at all, but a proposal for one. The proposal for a Green New Deal introduced in the U.S. Congress this year called for urgent government action to decarbonize our economy in a way that boosts employment and does not harm the weakest in society. This proposal in effect asks us to rethink what philosophers call the social contract between business, government, and society. That contract had already been cracked by the wealth and income gaps that have been widening since the 1980s. The threats of climate change have made this rethinking of the social contract even more urgent. No wonder, then, that in 2019 even the Business Roundtable proclaimed a new set of metrics for business that aims to balance the interests of shareholders and other stakeholders.

In 2019, we saw our planetary predicament more clearly than ever before. The business deals of the next decade will signal how we will respond. Some will reinforce existing habits, and more, one hopes, will transform our economy for the better.