By Ben Gomes-Casseres | Originally in PBS MAKING SEN$E | Portions of this article are from the author’s article in Harvard Business Review, which you can read here.

Editor’s Note: Ben Gomes-Casseres, author of “Remix Strategy: The Three Laws of Business Combinations,” pulls lessons from a trio of recent high-profile deal cancellations: Halliburton-Baker Hughes, Pfizer-Allergan and Staples-Office Depot.

This month marked the 100th anniversary of Louis Brandeis’ confirmation to the U.S. Supreme Court. Reading his passionate writings on the “curse of bigness” makes me wonder what Brandeis would think of today’s big mergers.

As it happens, anti-trust authorities have been active of late, questioning many of those mergers. And several have been stopped dead in their tracks — to the disappointment of the investment-banker descendants of the money houses that were Brandeis’s nemesis in the early 20th century.

What lies behind the recent wave of antitrust actions? Politics, perhaps — but the Obama administration has not been more active stopping mergers than previous administrations. But some of the recent deals were too rich or too clever for their own good, and others pushed industry consolidation one bridge too far. And probably ‘tis just the season for it — the wave of antitrust actions may just stem from last year’s bumper crop of merger announcements.

Let’s look at a trio of recent high-profile deal cancellations: Halliburton-Baker Hughes, Pfizer-Allergan and Staples-Office Depot. These mergers span a wide swath of American industry — from to oil and gas to pharmaceuticals and big-box retailing. This diversity suggests how varied the reasons are behind today’s mergers.

The classic reason for firms combining their assets is to remix them to create new value. But who captures that new value? Usually shareholders do so to some extent, otherwise they would not approve the merger. Beyond that, do consumers benefit or not? What is the impact on competition and rival companies? More broadly, is the new value truly a net benefit to society, or is it a transfer from one group to another? These larger societal questions are the kind exercised by Louis Brandeis and that today are addressed by various regulatory bodies.

READ MORE: Column: Why mergers are booming

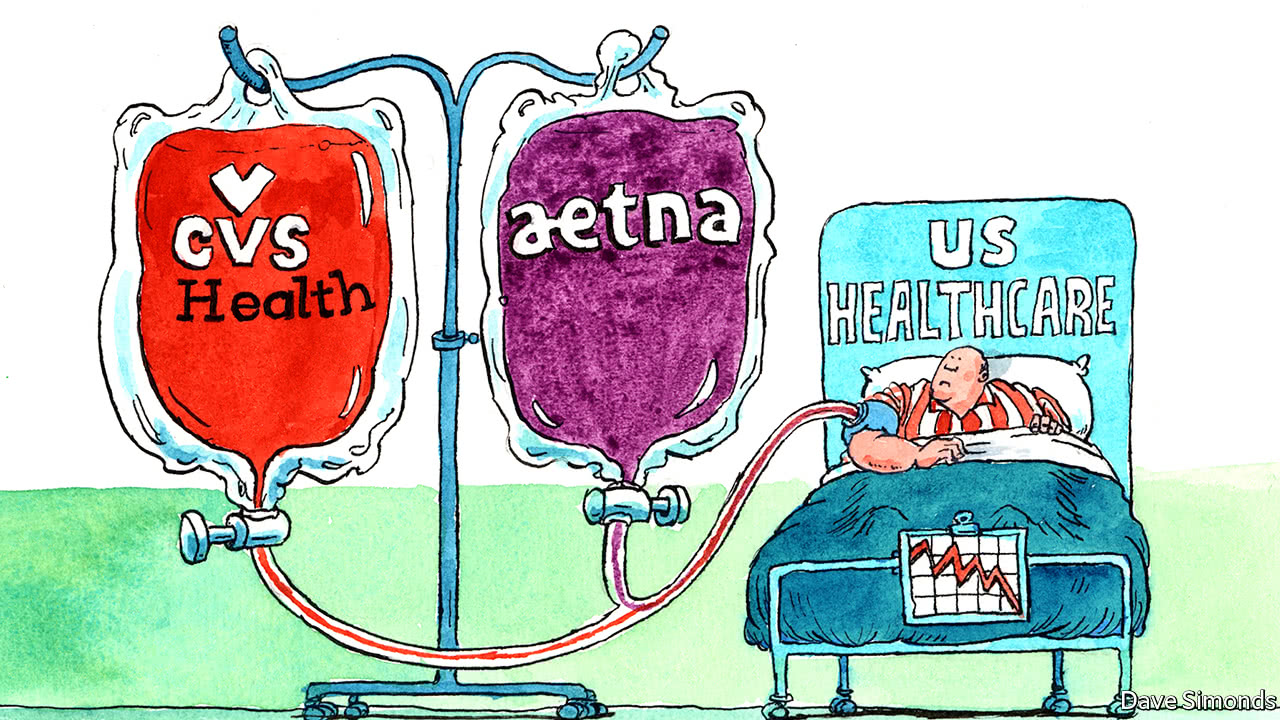

A careful look at these three deals shows how regulators think about these questions and leads to lessons for managers contemplating mergers in the future. (Several health care insurance mergers are up for review this summer, such as Cigna-Anthem.)

The Halliburton-Baker Hughes deal was a classic case of a bridge too far. And they knew it. Baker Hughes had resisted Halliburton’s overtures for months before agreeing to the deal, fearing that it would not pass anti-trust muster. It accepted the offer in the end only with a large break-up fee of $3.5 billion.

It did not take the Department of Justice much figuring to show that the merger of the number two and number three player oil field services would concentrate selling power substantially in 23 specific markets, from drilling fluids to drill bits. This would reduce options for customers (huge oil companies themselves) and could reduce innovation, they reasoned. And crucially, the Department of Justice did not see benefits to the concentration — no countervailing pro-competitive or efficiency effects that might have tilted the balance in favor of approval. Open and shut case, they said. It took only a few weeks for the deal makers to scuttle their plan, without much of a fight.

This case highlights the second lesson of the season: It is tough to argue that long term good will come from short term pain. Corporate leaders in the U.S. now see that there are greater hurdles to cross in thinking through, structuring and presenting such strategic arguments. In the end, that is a good thing.

The third lesson from the merger-busting climate is that alternatives to merger will become more attractive. The global airline industry for a long time has managed to do with alliances what other industries do with mergers – because they are blocked from cross-border mergers for the most part.