By Ben Gomes-Casseres | Originally in HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW |

Corporate marriage brokers are again fully employed. Every day a new deal is announced, often in reaction to yesterday’s deal. As a consequence, the business landscape is changing.

Take pharmaceuticals. In the last couple of months, Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline joined in a series of deals(valued at about $25 billion) and Bayer followed soon after with the purchase of a division of Merck (for about $14 billion). Pfizer’s pursuit of Astra-Zeneca has been called off for now, but don’t be surprised if it comes back, or if the companies find other ways to recombine their assets. Valeant’s bid to acquire Allergan is the most controversial. Companies in other industries, too, are following such combination strategies. And they too are watching their backs—as Andy Grove said, “only the paranoid survive.” Chief rivals in an industry often seek to match each other’s capabilities, lest they fall behind. For example, AT&T and DirecTV were prompted to conclude their merger deal after Comcast and Time Warner announced theirs; the long-discussed merger between Sprint and T-Mobile may not be far behind.

Many of the deals we’re seeing today are not “merger-as-usual”—they are more nuanced ways to remix business assets than what we have seen before. All these types of deals combine the assets of different players to create new value. For example, as blockbuster drug patents expire, the pharmaceutical companies are looking for more nuanced ways to build competitive advantage by focusing on specialties or building scale in over-the-counter medicines

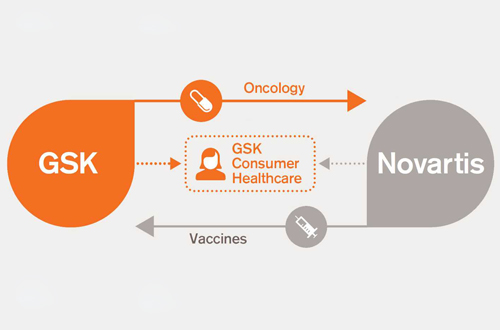

Take the Novartis-GSK deals. This is not a slap-them-together merger of pharma giants. Novartis will slice off its vaccines business and sell it to GSK. GSK in turn will slice off its cancer business, and sell it to Novartis. The two companies will transfer their consumer healthcare businesses into a new joint venture that will be owned two-thirds by GSK and one-third by Novartis. It is enough to make your head spin.

To succeed, Novartis and GSK will need to manage carefully the separation of each business from its home-base, the grafting of the business onto its new base, and heal the wounds left from the procedure. Good thing that they are already adept at genetic engineering—this looks like a careful re-engineering of the DNA of each company.

Furthermore, Novartis and GSK will now be tied at the hip in more ways than one. The consumer-healthcare joint venture is an obvious linkage. Beyond that, the asset sales include ongoing royalties and payments that are contingent on milestones or on the results of future trials. In other words, these deals will be far from done when they are signed—their payoff will depend critically on how well the post-deal processes are managed. If you have successful experience managing a partnership, polish your resume. It has become invaluable.

Deal-making was always a hot profession, attracting top consultants and lawyers; all the while, deal-managing usually took a back seat. This is changing. In the last decade or so, many firms have built up capabilities in alliance management—this has become a profession, with its own methods, training needs, and career paths. Pharmaceutical companies have been in the forefront of this trend; they compete openly on being a “partner of choice.”

Mastering partnership skills often demands taking on a new perspective. For too long, you have been told to take care of your own—stick to your knitting, stay true to your “company DNA,” and so on. Today, a firm holding on to its DNA when the world around it is changing will end up like the extinct Dodo bird.

Take a cue from the deals you see daily now: Look outside your business for new sources of competitive advantage. The Not-Invented-Here syndrome is so 20th century. The future strength of your business is as likely to come from resources you don’t own outright—or own yet—as it is from assets you already own.